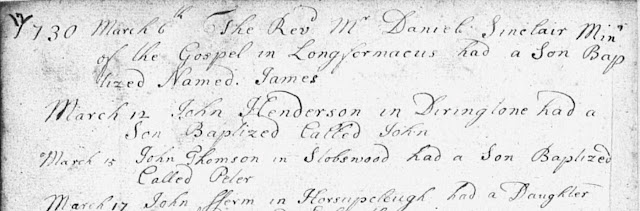

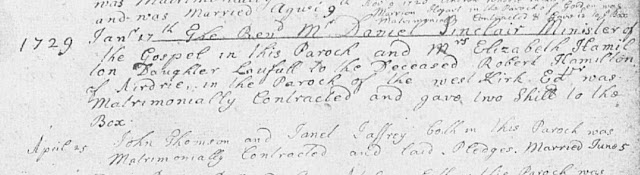

September 24th, 1771 Arthur St. Clair to William Allen

- Courtesy Stan Klos

By 1774 Arthur St. Clair had risen in favor and was appointed

the Magistrate, as well as Prothonotary, in the newly formed

Westmoreland County. Colonial Virginia was in a bitter border

dispute with the Penn's of Pennsylvania over large parts of the

new Pennsylvania County including Fort Pitt.

In 1758 General Forbes, along with Colonel Washington, took

command of the Ohio River junction from the French garrison who

had burnt Fort Duquesne in their flight to Canada. The Fort

had been burnt beyond repair but the garrison left

behind to secure the source of the Ohio River needed shelter

from the winter. Colonel Hugh Mercer was charged as the

commander and oversaw fortification construction on the banks

of the Monongahela River 1000 or so feet from where it flowed

in the Allegheny River forming the Ohio River. Fort

Mercer was completed in January 1759 and was large enough to

shelter a force of 400 men. Here soldiers, engineers,

indigenous people, and citizens labored for 19 months to

construct an elaborate fortress on the three rivers triangle

consisting of two acres inside the fortress walls and 18 more

inside the outer earthen works.

Fort Pitt was considered royal possession. The western

Pennsylvania roads leading to the fort were constructed during

the Forbes Campaign open the area to settlement by

Pennsylvanians. Three years earlier, roads were

constructed by General Braddock’s during his campaign to

capture Fort Duquesne through the Virginia wilderness.

Braddock’s force were routed by the French and forced into

retreat after advancing to present day Braddock, Pennsylvania

on the Monongahela River.

General Braddock was mortally wounded in the battle and

of the

1,300 men he had led in the campaign, 456 were killed and 422

wounded. Braddock’s road, however, remained intact

opening the northern Ohio Valley for future settlement by

Virginians. Both colonies, therefore, were poised to claim Fort

Pitt once the British forces withdrew ending the royal

jurisdiction over the territory.

Peace between the colonies had reigned at Fort Pitt for

the years while it was garrisoned by British troops.

A decision, however, was finally made to withdraw

British troops from Fort Pitt due to debts incurred over the

War for Empire better known as the French and Indian War in the

North American theater. In 1772, thirteen years

after it was built, the fort was sold by Captain Charles E.

Edmonstone of the 18th Royal Regiment to Alexander Ross and

William Thompson for fifty pounds of New York colonial

currency. The construction materials that were used in the

outer fort’s embankments were dismantled and utilized in the

construction of buildings that would eventually form the

earliest structure of the “Pittsburg” settlement. Jurisdiction

over the region passed from the English Crown to the

Pennsylvania Colony.

This did not settle the Boundary disputes between Pennsylvania

and Virginia. To protect its interest Pennsylvania, with

permission from the Crown, garrisoned a colonial militia to

protect the fort. This action did not deter Colonial Governor

Lord Dumore who insisted the land claims to the region,

including the settlement of Pittsburg, belong to Virginia.

On January 6, 1774, Dunmore commissioned and sent

Dr. John Connolly to Fort Pitt as the "Captain and

Commandant of Pittsburgh and its dependencies." Connolly

began rising a militia from local Virginians who quickly

garrisoned the dilapidated fort for Lord Dumore.

The fort, upon Connolly’s seizure, was renamed Fort Dumore in

honor of the Colonial Governor. Commandant Connolly

then issued a Fort Dumore Proclamation, calling on the people

of Western Pennsylvania to meet him, as a militia, on the 25th

of January 1774. Arthur St. Clair who was the King's

magistrate of Westmoreland County, founded only year earlier on

February 26, 1773 encompassing the fort, was appalled by

Connolly's seizure and issued a warrant for his arrest.

Connolly was captured and imprisoned by Magistrate St. Clair in

the jail at Hannastown, the Westmoreland County

seat.

In asserting the claims of Virginia, Lord Dumore insisted that

Magistrate St. Clair should be punished for his temerity in

arresting his Captain by dismissal from office. Governor Penn

declined to remove St. Clair instead commending him as a

superior magistrate by first providing proper legal notice to

Mr. Connolly who was only arrested after he refused to

surrender the Fort. Governor Penn wrote Governor Dumore

on March 31, 1774:

I am truly concerned that you should think the commitment of

Mr. Conolly so great an insult on the authority of the

Government of Virginia, as nothing less than Mr. St. Clair's

dismission from his offices can repair. The lands in the

neighbourhood of Pittsburg were surveyed for the Proprietaries

of Pennsylvania early in the year 1769, and a very rapid

settlement under this Government soon took place, and

Magistrates were appointed by this Government to act there in

the beginning of 1771, who have ever since administered justice

without any interposition of the Government of Virginia till

the present affair. It therefore could not fail of being both

surprising and alarming that Mr. Conolly should appear to act

on that stage under a commission from Virginia, before any

intimation of claim or right was ever notified to this

Government. The advertisement of Mr. Conolly had a strong

tendency to raise disturbances, and occasion a breach of the

public peace, in a part of the country where the jurisdiction

of Pennsylvania hath been exercised without objection, and

therefore Mr. St. Clair thought himself bound, as a good

Magistrate, to take a legal notice of Mr. Conolly.

Mr. St. Clair is a gentleman who for a long time had the honour

of serving his Majesty in the regulars with reputation, and in

every station of life has preserved the character of a very

honest worthy man; and though perhaps I should not, without

first expostulating with you on the subject, have directed him

to take that step, yet you must excuse my not complying with

your Lordship' s requisition of stripping him, on this

occasion, of his offices and livelihood, which you will allow

me to think not only unreasonable, but somewhat

dictatorial.

I should be extremely concerned that any misunderstanding

should take place between this Government and that of Virginia.

I shall carefully avoid every occasion of it, and shall always

be ready to join you in the proper measures to prevent so

disagreeable an incident, yet I cannot prevail on myself to

accede in the manner you require, to a claim which I esteem,

and which I think must appear to everybody else to be

altogether groundless.

[2]

Counter arrests and much correspondence followed, but the

controversy was soon obscured by the stirring events of Lord

Dunmore's War. Disturbances were renewed by Connolly on several

border fronts and once again he was arrested. The Virginia

Colonial Governor ordered the counter arrest of three of the

Pennsylvania justices and in an exchange Connolly was released.

The boundary troubles between Virginia and Pennsylvania were

finally settled by the Continental Congress while Arthur St.

Clair was commissioned in the Revolutionary War.

Arthur St. Clair was appointed a colonel of one of the

Pennsylvania regiments and received his recruiting orders on

the 10th of January, 1776. Colonel St. Clair raised and trained

a regiment in the dead of winter. He then marched six companies

of the regiment from Pennsylvania to Canada, a distance of

several hundred miles, and joined the American army in Quebec

on April 11th, 1776.

General Montgomery, who in the fall of 1775 defeated the

British at Chamblee, St. Johns, and Montreal, gave Congress a

fair prospect of expelling the British from Canada annexing

that province to the United Colonies. Unfortunately the General

was defeated and killed before St. Clair's arrival after the

disastrous affair at Three Rivers. St. Clair, therefore, could

only aid General Sullivan in the retreat as second in command

under General Thompson. St. Clair's familiarity with British

military strategy and the Canadian wilderness were key assets

that helped save the Northern army from capture.

According to 18th Century military historian David

Ramsay:

The Americans were soon repulsed and forced to retreat. In the

beginning of the action General Thomson left the main body of

his corps to join that which was engaged. The woods were so

thick, that it was difficult for any person in motion, after

losing sight of an object to recover it. The general therefore

never found his way back. The situation of Colonel St. Clair,

the next in command became embarrassing. In his opinion a

retreat was necessary, but not knowing the precise situation of

his superior officer, and every moment expecting his return, he

declined giving orders for that purpose. At last when the

British were discovered on the river road, advancing in a

direction to gain the rear of the Americans, Colonel St. Clair

in the absence of General Thomson, ordered a

retreat.

Colonel St. Clair having some knowledge of the country from his

having served in it in the preceding war, gave them a route by

the Acadian village where the river de Loups is fordable. They

had not advanced far when Colonel St. Clair found himself

unable to proceed from a wound, occasioned by a root which had

penetrated through his shoe. His men offered to carry him, but

this generous proposal was declined. He and two or three

officers, who having been worn down with fatigue, remained

behind with him, found an asylum under cover of a large tree

which had been blown up by the roots. They had not been long in

this situation when they heard a firing from the British in

almost all directions. They nevertheless lay still, and in the

night stole off from the midst of surrounding foes. They were

now pressed with the importunate cravings of hunger, for they

were entering on the third day without food. After wandering

for some time, they accidentally found some peasants, who

entertained them with great hospitality. In a few days they

joined the army at Sorel, and had the satisfaction to find that

the greatest part of the detachment had arrived safe before

them. In their way through the country, although they might in

almost every step of it have been made prisoners, and had

reason to fear that the inhabitants from the prospect of

reward, would have been tempted to take them, yet they met with

neither injury nor insult. General Thomson was not so

fortunate. After having lost the troops and falling in with

Colonel Irwine, and some other officers, they wandered the

whole night in thick swamps, without being able to find their

way out. Failing in their attempts to gain the river, they had

taken refuge in a house, and were there made prisoners.

[3]

In recognition of this service St. Clair was promoted to

Brigadier-General on August 9th, 1776 and ordered to join

George Washington to organize the New Jersey militia. Ramsay

reports of these desperate times:

This retreat into, and through New-Jersey, was attended with

almost every circumstance that could occasion embarrassment,

and depression of spirits. It commenced in a few days, after

the Americans had lost 2700 men in Fort Washington. In fourteen

days after that event, the whole flying camp claimed their

discharge. This was followed by the almost daily departure of

others, whose engagements terminated nearly about the same

time. A farther disappointment happened to General Washington

at this time. Gates had been ordered by Congress to send two

regiments from Ticonderoga, to reinforce his army. Two Jersey

regiments were put under the command of General St. Clair, and

forwarded in obedience to this order, but the period for which

they were enlisted was expired, and the moment they entered

their own state, they went off to a man. A few officers without

a single private were all that General St. Clair brought off

these two regiments, to the aid of the retreating American

army. The few who remained with General Washington were in a

most forlorn condition. They consisted mostly of the troops

which had garrisoned Fort Lee, and had been compelled to

abandon that post so suddenly, that they commenced their

retreat without tents or blankets, and without any utensils to

dress their provisions. In this situation they performed a

march of about ninety miles, and had the address to prolong it

to the space of nineteen days. As the retreating Americans

marched through the country, scarcely one of the inhabitants

joined them, while numbers were daily flocking to the royal

army, to make their peace and obtain protection. They saw on

the one side a numerous well appointed and full clad army,

dazzling their eyes with the elegance of uniformity; on the

other a few poor fellows, who from their shabby cloathing were

called ragamuffins, fleeing for their safety. Not only the

common people changed sides in this gloomy state of public

affairs, but some of the leading men in New-Jersey and

Pennsylvania adopted the same expedient. Among these Mr.

Galloway, and the family of the Allens of Philadelphia, were

most distinguished. The former, and one of the latter, had been

members of Congress. In this hour of adversity they came within

the British lines, and surrendered themselves to the

conquerors, alleging in justification of their conduct, that

though they had joined with their countrymen, in seeking for a

redress of grievances in a constitutional way, they had never

approved of the measures lately adopted, and were in

particular, at all times, averse to independence.

On the day General Washington retreated over the Delaware, the

British took possession of Rhode-Island without any loss, and

at the same time blocked up commodore Hopkins' squadron, and a

number of privateers at Providence.[4]

When George Washington and St. Clair retreated over the

Delaware, the boats and barges along the east side of the

Delaware River were removed and garrisoned by the remnants of

the Continental Army. This act halted the progress of the

British Forces into Pennsylvania in the winter months of

November and December. The English commanders, sure of eminent

conquest once the Delaware River froze, deployed their army in

Burlington, Bordentown, Trenton, and on other waterfront towns

in New Jersey.

On the Pennsylvania side of the river, General Washington

ordered Generals Sullivan and St. Clair to recruit and train

troops as the Continental Army was in desperate need of

reformation. Together, with the Philadelphia troop recruiting

successes of General Mifflin, Sullivan and St. Clair raised

over 2000 new troops to support the Revolution. St. Clair and

Sullivan joined Washington's beleaguered 400 troops in

Pennsylvania and prepared for Washington's Delaware crossing to

Trenton, New Jersey. On Christmas night 1776 St. Clair's

Continental troops, now under Washington's command, crossed

into New Jersey and attacked the Hessians at dawn on the 26th.

Twenty-two Hessians were killed, 84 wounded and 918 taken

prisoner. Ramsay account of the surprise attack states:

Of all events, none seemed to them more improbable, than that

their late retreating half naked enemies, should in this

extreme cold season, face about and commence offensive

operations. They [The British] indulged themselves in a degree

of careless inattention to the possibility of a surprise, which

in the vicinity of an enemy, however contemptible, can never be

justified. It has been said that colonel Rahl, the commanding

officer in Trenton, being under some apprehension for that

frontier post, applied to general Grant for a reinforcement,

and that the general returned for answer. 'Tell the colonel, he

is very safe, I will undertake to keep the peace in New-Jersey

with a corporal's guard.'

In the evening of Christmas day, General Washington, made

arrangements for recrossing the Delaware in three divisions; at

M. Konkey's ferry, at Trenton ferry, and at or near Bordentown.

The troops which were to have crossed at the two last places

were commanded by generals Ewing, and Cadwallader, they made

every exertion to get over, but the quantity of ice was so

great, that they could not affect their purpose. The main body

which was commanded by General Washington crossed at M.

Konkey's ferry, but the ice in the river retarded their passage

so long, that it was three o'clock in the morning, before the

artillery could be got over. On their landing in Jersey, they

were formed into two divisions, commanded by general Sullivan,

and Greene, who had under their command brigadiers, lord

Stirling, Mercer and St. Clair: one of these divisions was

ordered to proceed on the lower, or river road, the other on

the upper or Pennington road. Col. Stark, with some light

troops, was also directed to advance near to the river, and to

possess himself of that part of the town, which is beyond the

bridge. The divisions having nearly the same distance to march

were ordered immediately on forcing the out guards, to push

directly into Trenton, that they might charge the enemy before

they had time to form. Though they marched different roads, yet

they arrived at the enemy's advanced post, within three minutes

of each other. The out guards of the Hessian troops at Trenton

soon fell back, but kept up a constant retreating fire. Their

main body being hard pressed by the Americans, who had already

got possession of half their artillery, attempted to file off

by a road leading towards Princeton, but was checked by a body

of troops thrown in their way. Finding they were surrounded,

they laid down their arms. The number which submitted was 23

officers, and 885 men. Between 30 and 40 of the Hessians were

killed and wounded. Colonel Rahl, was among the former, and

seven of his officers among the latter. Captain Washington of

the Virginia troops, and five or six of the Americans were

wounded. Two were killed, and two or three were frozen to

death. The detachment in Trenton consisted of the regiments of

Rahl, Losberg, and Kniphausen, amounting in the whole to about

1500 men, and a troop of British light horse. All these were

killed or captured, except about 600, who escaped by the road

leading to Bordentown.

The British had a strong battalion of light infantry at

Princeton, and a force yet remaining near the Delaware,

superior to the American army. General Washington, therefore in

the evening of the same day, thought it most prudent to

re-cross into Pennsylvania, with his prisoners.

The effects of this successful enterprise were speedily felt in

recruiting the American army. About 1400 regular soldiers,

whose time of service was on the point of expiring, agreed to

serve six weeks longer, on a promised gratuity of ten paper

dollars to each. Men of influence were sent to different parts

of the country to rouse the militia. The rapine, and impolitic

conduct of the British, operated more forcibly on the

inhabitants, to expel them from the state, than either

patriotism or persuasion to prevent their overrunning

it.

On the 28th, Washington re-crossed the Delaware and took

possession of Trenton. The British detachments that had been

distributed over the New Jersey river towns had now assembled

at Princeton. These troops were also reinforced by a British

detachment from New Brunswick, N.J. commanded by General

Cornwallis. From this position the English planned to overwhelm

Washington, by sheer numbers, hoping to defeat the Continental

Army on January 2nd. Realizing this Washington carefully

considered his options. A retreat to the city of Philadelphia

would have shattered the Continental Army's confidence that

permeated the new nation after their Victory at Trenton. George

Washington decided to stand, fight and see what opportunities

may arise in the heat of what would be a manageable late

afternoon battle. The Continental forces readied their

defenses.

[5]

The British began their advance from Princeton at 4 P.M.

attacking a body of Americans that were posted with four field

pieces just north of Trenton. This overwhelming military action

required the forces to retreat over Assunpink Creek. Here

Washington had posted cannons on the opposite banks of the

creek. The cannons, together with musket fire, stalemated the

pursuing British at the bottleneck created by the bridge. The

British fell back out of reach of the cannons, and made camp

for the night. The Americans remained defiantly camped on the

other side cannonading the enemy until late in the

evening.

Washington called a council of war that night on January 2,

1777 with his troops camped along Assunpink Creek. Many of St.

Clair's Biographers, and even St. Clair himself, claim that the

movement that culminated in the Victory at Princeton the

following day was his recommendation to the council. The

General's biographers purport that not only did St. Clair

direct the details of the march but also his own brigade

marched at the head of the advancing army.

Washington's decision to go around the British lines at night

and advance on Princeton was brilliant. The plan was a smashing

success and British losses were estimated at 400 to 600 killed,

wounded or taken prisoner. General Cornwallis and his troops

were forced to withdraw into Northern New Jersey to protect key

towns recently conquered by the British. Ramsay reports on the

battle:

The next morning presented a scene as brilliant on the one

side, as it was unexpected on the other. Soon after it became

dark, General Washington ordered all his baggage to be silently

removed, and having left guards for the purpose of deception,

marched with his whole force, by a circuitous route to

Princeton. This maneuver was determined upon in a council of

war, from a conviction that it would avoid the appearance of a

retreat, and at the same time the hazard of an action in a bad

position, and that it was the most likely way to preserve the

city of Philadelphia, from falling into the hands of the

British. General Washington also presumed, that from an

eagerness to efface the impressions, made by the late capture

of Hessians at Trenton, the British commanders had pushed

forward their principal force, and that of course the remainder

in the rear at Princeton was not more than equal to his own.

The event verified this conjecture. The more effectually to

disguise the departure of the Americans from Trenton, fires

were lighted up in front of their camp. These not only gave an

appearance of going to rest, but as flame cannot be seen

through, concealed from the British, what was transacting

behind them. In this relative position they were a pillar of

fire to the one army, and a pillar of a cloud to the other.

Providence favoured this movement of the Americans. The weather

had been for some time so warm and moist, that the ground was

soft and the roads so deep as to be scarcely passable: but the

wind suddenly changed to the northwest, and the ground in a

short time was frozen so hard, that when the Americans took up

their line of march, they were no more retarded, than if they

had been upon a solid pavement.

General Washington reached Princeton, early in the morning, and

would have completely surprised the British, had not a party,

which was on their way to Trenton, descried his troops, when

they were about two miles distant, and sent back couriers to

alarm their unsuspecting fellow soldiers in their rear. These

consisted of the 17th, the 40th, & 55th regiments of

British infantry and some of the royal artillery with two field

pieces, and three troops of light dragoons. The center of the

Americans, consisting of the Philadelphia militia, while on

their line of March, was briskly charged by a party of the

British, and gave way in disorder. The moment was critical.

General Washington pushed forward, and placed himself between

his own men, and the British, with his horse's head fronting

the latter. The Americans encouraged by his example, and

exhortations, made a stand, and returned the British fire. The

general, though between both parties, was providentially

uninjured by either. A party of the British fled into the

college and were there attacked with field pieces which were

fired into it. The seat of the muses became for some time the

scene of action. The party which had taken refuge in the

college, after receiving a few discharges from the American

field pieces came out and surrendered themselves prisoners of

war. In the course of the engagement, sixty of the British were

killed, and a greater number wounded, and about 300 of them

were taken prisoners. The rest made their escape, some by

pushing on towards Trenton, others by returning towards

Brunswick. The Americans lost only a few, but colonels Haslet

and Potter, and Captain Neal of the artillery, were among the

slain. General Mercer received three bayonet wounds of which he

died in a short time. He was a Scotchman by birth, but from

principle and affection had engaged to support the liberties of

his adopted country, with a zeal equal to that of any of its

native sons. In private life he was amiable, and his character

as an officer stood high in the public esteem.

While they were fighting in Princeton, the British in Trenton

were under arms, and on the point of making an assault on the

evacuated camp of the Americans. With so much address had the

movement to Princeton been conducted, that though from the

critical situation of the two armies, every ear may be supposed

to have been open, and every watchfulness to have been

employed, yet General Washington moved completely off the

ground, with his whole force, stores, baggage and artillery

unknown to, and unsuspected by his adversaries. The British in

Trenton were so entirely deceived, that when they heard the

report of the artillery at Princeton, though it was in the

depth of winter, they supposed it to be thunder: The Battle of

Princeton was another important Continental Victory as it

further raised the moral of the troops and the nation. The

surprised British troops quickly evacuated Princeton on the

onslaught and to Washington's delight; they re-deployed their

troops from quartering Bordentown and Trenton to New Brunswick.

The British also decided to evacuate their troops from Newark

and Woodbridge holding under force only Amboy, along with New

Brunswick, in Central New Jersey. The British retreat from the

victories of Trenton and Princeton sparked a resurrection of

patriotism that kept George Washington and his troops

invigorated throughout the winter of 1777.[6]

General Washington, upon St. Clair's council, made the decision

to winter in Morristown because its passes and hills afforded

geographical shelter to his suffering army. The negative

outlook that had ceased these United States of America in the

fall of 1776 had all but dissipated in the northern hills of

New Jersey. Recruiting that had been painfully measured just

before the Battle of Trenton was successfully rehabilitated. It

soon became clear to everyone that George Washington would

quickly organize and train a permanent regular force to resume

the offensive in the spring.

While in Morristown, the New Jersey militia was re-charged and

conducted several successful skirmishes killing forty and fifty

Waldeckers at Springfield. These were the same soldiers who

were, but a month before, overrun by the British without even

meager opposition. George Washington

remained, throughout his incredible life, steadfastly loyal to

Arthur St. Clair recognizing the Pennsylvania general's deeds

and council during the campaigns against Trenton and Princeton.

It was a beginning of a friendship that would positively serve

the United States, beyond anyone's expectations, for the next

24 years. For his service in 1776 and 1777 St. Clair was

promoted to Major-General.

Arthur St. Clair's next call to action was by John Hancock who

ordered him to defend Fort Ticonderoga. This upstate New York

fort was built to control the strategic route between the St.

Lawrence River in Canada and the Hudson River to the south.

Overlooking the outlet of Lake George into Lake Champlain, it

was considered a key to the continent. The fort was used in the

War for Empire and largely abandoned except for British

military stores that remained there at the beginning of the

Revolution. In 1775, Ethan Allen and Benedict Arnold surprised

the British and captured Fort Ticonderoga. The cannons and

armaments were used in the siege of Boston, which drove the

British out of Massachusetts. The fort was garrisoned with

12,000 troops to counter any invading force coming into America

from Canada.

In 1776 with Washington's losses troops deserted and were moved

to more pressing posts in Pennsylvania and New Jersey. By the

spring of 1777 Fort Ticonderoga had fallen in disrepair with

only a handful of troops protecting the northern passage When

it became clear that the British, under General Burgoyne, were

marching to retake the position, Congress hastily ordered Major

General Arthur St. Clair to command and defend Fort

Ticonderoga, by a letter:

Philadelphia, April 30, 1777 John Hancock to Arthur St.

Clair - Courtesy of Stan Klos

To: Maj. Gen. Arthur St. Clair.

Sir:

-- The

Congress having received intelligence of the approach of the

enemy towards Ticonderoga have thought proper to direct you to

repair thither without delay. I have it therefore in charge to

transmit the enclosed resolve [not present] and to direct that

you immediately set out on the receipt

hereof.

John Hancock, Presidt.

Major-General St. Clair arrived in early June and set about

preparations for defense. Although Congress desperately wanted

to retain Fort Ticonderoga, St. Clair was only spared some

2,500 men and scarce provisions to hold it. A minimum garrison

of 10,000 men was required to check the British advance.

Burgoyne's army consisted of 8,000 British regulars and 2,500

auxiliary troops.

In preparation, St. Clair's

force was too small to cover all exposed points. In his

scramble to post his men St. Clair made the decision not to

fortify the steep assent to the mountain top which he deemed

impassable for heavy artillery.

When British arrived

in the area, he was proved disastrously wrong because Burgoyne

outflanked him by hauling his artillery batteries atop nearby

Mount Defiance. The British were now capable of bombarding Fort

Ticonderoga without fear of retaliation by the

Americans.

St. Clair and his officers held a council of war, and decided

to evacuate the fort. Matthias Alexis Roche de Fermoy, by

orders of Congress, and against the protest of George

Washington was made the commander of Fort Independence,

opposite Fort Ticonderoga. Fermoy made a grave military error

that almost caused St. Clair the loss of a large number of his

forces. Upon the retreat of St. Clair from Ticonderoga, Fermoy

set fire to his quarters on Mount Independence at two o'clock

on the morning of July 6th, 1777 thus revealing to Burgoyne St.

Clair's evacuation of Fort Ticonderoga. Had it not been for

this, St. Clair would have made good his retreat with minimal

causalities and loss of his supplies.

St. Clair fled through the woods, leaving a part of his force

at Hubbardto. These troops were attacked and defeated by

General Fraser on July 7th, 1777, after a well-contested

battle. On July12th, St. Clair reached Fort Edward with the

remnant of his men. St. Clair reported:

"I know I could have saved my reputation by sacrificing the

army; but were I to do so, I should forfeit that which the

world could not restore, and which it cannot take away, the

approbation of my own conscience".[7]

St. Clair's action forced General Burgoyne to divide his forces

between pursuit of St. Clair and garrisoning Fort Ticonderoga.

Burgoyne, after a long and arduous trek through the New York

frontier, made an unsuccessful attempt to break through

American Forces and Capture Saratoga. Burgoyne retreated and

ordered his troops to entrench in the vicinity of the Freeman

Farm. Here he decided to await support from Clinton, who was

supposedly preparing to move north toward Albany from New York

City. He waited for three weeks but Clinton never came. With

his supply line cut and a growing Continental Army he decided

to attack on October 7th ordering a recon-naissance-in-force to

test the American left flank. This attack was unsuccessful and

Burgoyne loss General Fraser primarily due to Benedict Arnold's

direct counter-attack against the British Center.

That evening the British retreated but kept their campfires

burning brightly to mask their withdrawal. Burgoyne's troops

took refuge in a fortified camp on the heights of Saratoga.

Clinton never arrived, the Continental Forces swelled to over

20,000. Faced with overwhelming numbers, Burgoyne surrendered

on October 17, 1777 to General Horatio Gates who was hailed

the "Hero

of Saratoga". This

was one of the great American victories of the war and made the

British retention of Fort Ticonderoga untenable. This surrender

shocked the European Nations and direly needed foreign aid

poured into US coffers from France and the Netherlands.

Despite this positive outcome General St. Clair was accused of

cowardice by the same faction (Conway Cabal) that

sought the ousting of George Washington as Commander-in-Chief

for "The

Hero of Saratoga".

George Washington supported St. Clair’s position who remained

with his army throughout the court-martial process. St. Clair

was with Washington at Brandywine on September 11th, 1777,

acting as voluntary aide.

The Court met August 25th, 1778, and continued the examination

of witnesses until September 29th with General Benjamin Lincoln

as its President. The charges were: neglect of duty,

cowardice, treachery, incapacity as a General, and shamefully

abandoning the posts of Ticonderoga and Mount

Independence.

General St. Clair testified in his own defense on September 29

which those in attendance found to be very able and

complete. The court acquitted him stating:

Indeed, from the knowledge I had of the country through which

General Burgoyne had to advance, the difficulties I knew he

would be put to subsist his army, and the contempt

he would naturally have for an enemy whose retreat I concluded

he would ascribe to fear, I made no doubt he would soon be so

far engaged, as that it would be difficult for him either to

advance or retreat. The event justified my conjecture, but

attended with consequences beyond my most sanguine

expectations. A fatal blow given to the power and insolence of

Great Britain, a whole army prisoners, and the reputation of

the arms of America high in every civilized part of the world!

But what would have been the consequences had not the steps

been taken, and my army had been cut to pieces or taken

prisoners? Disgrace would have been brought upon our arms and

our counsels, fear and dismay would have seized upon the

inhabitants, from the false opinion that had been formed of the

strength of these posts, wringing grief and moping melancholy

would have filled the now cheerful habitations of those whose

dearest connections were in that army, and a lawless host of

ruffians, set loose from every social tie, would have roamed at

liberty through the defenseless country, whilst hands of

savages would have earned havoc, devastation, and terror before

them! Great part of the State of New York must have submitted

to the conqueror, and in it he could have found the means to

enable him to prosecute his success. He would have been able

effectually to have co-operated with General Howe, and would

probably have soon been in the same country with him; that

country where our illustrious General, with an inferior force,

made so glorious a stand, but who must have been obliged to

retire if both armies came upon him at once, or might have been

forced, perhaps, to a general and decisive action in

unfavorable circumstances, where by the hopes, the now

well-founded hopes of America, of liberty, of peace and safety,

might have been cut off forever. Every consideration seems to

prove the propriety of the retreat, that I could not undertake

it sooner, and that, had it been delayed longer, it had been

delayed too long.

The Court, having duly considered the charges against

Major-General St. Clair, and the evidence, are unanimously of

opinion that he is Not Guilty of either of the charges against

him, and do unanimously acquit him of all and every of them

with the highest honor. B. Lincoln, President.

[8]

Lafayette wrote to St. Clair,

I cannot tell you how much my heart was interested in

anything that happened to you and how I rejoiced, not that you

were acquitted, but that your conduct was examined.[9]

John Paul Jones wrote,

I pray you be assured that no man has more respect for your

character, talents, and greatness of mind than, dear General,

your most humble servant.

St. Clair assignment after the ordeal was to assist General

John Sullivan in preparing his expedition against the Six

Nations and later was appointed a commissioner to arrange a

cartel against the British at Amboy on March 9th, 1780. St

Clair was then appointed to command the corps of light infantry

in the absence of Lafayette, but did not serve, owing to the

return of General George Clinton. He was a member of the

court-martial that condemned Major Andre, commanded at West

Point in October 1780, and aided in suppressing the mutiny in

the Pennsylvania line in January 1781.

St. Clair remained active during the 1780's Campaigns raising

troops and forwarding them to the south to Lafayette and

Washington. Congress in an attempt to protect Philadelphia from

another British occupation ordered St. Clair's to round up

troops to defend the city from what was believed to be an

imminent attack by General Clinton:

By the United States in Congress Assembled September 19,

1781

Ordered that Major General St. Clair cause the levies of

the Pennsylvania line now in Pennsylvania to rendezvous at or

near Philadelphia with all possible exposition.

Extract

from the minutes

Charles

Thompson

Specifically the Journals of the Continental Congress

reported:

The report of the committee on the letter from Major General

St. Clair was taken into consideration; Whereupon, The

Committee to whom were referred the letter of the 28th. of

August last from Major General St Clair, beg leave to report--

That they have conferred with the Financier on the subject of

the advance of money requested by General St Clair for officers

and privates of the Pennsylvania line, and that he informs your

Committee that it is not in his power to make the said

advances--

That your Committee know of no means which enables Congress at

present to make the advance requested by General St Clair: and

they are therefore of opinion that his application ought to be

transmitted to his Excellency the President and the Supreme

Executive of the State of Pennsylvania with an earnest request

that they will take the most effectual measures in their power

to enable General St Clair to expedite the march of the troops

mentioned in his letter.

Ordered, That the application of Major General St. Clair be

transmitted to his Excellency the president and the supreme

executive council of the State of Pennsylvania and they be

earnestly requested to take the most effectual measures in

their power to enable General St. Clair to expedite the march

of the troops mentioned in his letter.[10]

Washington continued he maneuvers surrounding Cornwallis at

Yorktown. When Congress realized that the British were not

going to attack Philadelphia; orders were hastily given to St.

Clair to move his forces south to Yorktown. St. Clair joined

Washington at Yorktown only four days before the surrender of

Lord Cornwallis.

In November he was placed in command of a body of troops to

join General Nathanael Greene, and remained in the south until

October 1782. St. Clair writes of this period:

When the army marched to the southward, I was left in

Pennsylvania to organize and forward the troops of that State

and bring up the recruits that had been raised there. The

command of the American Army was kept open for, the General

intending to take it upon himself. Formally, the command of the

allied army, which hitherto he ha had only done actually. After

sending off the greatest part of that line under General

Anthony Wayne, and on the point of following them, Congress

became alarmed that some attempt on Philadelphia would be made

from New York, in order to diver General Washington from his

purpose against Lord Cornwallis, and they ordered me to remain

with the few troops I had left, to which it was purposed to add

a large body of militia, and to form a camp on the Delaware: of

this I immediately apprised Washington, who had written to me,

very pressingly, to hasten on the reinforcements of that State;

informing me of the need he had of them, and, as he was pleased

to say, of my services also. He wrote again on the receipt of

my letter, in a manner still more pressing, and I laid that

letter before Congress, who, after considerable delay and much

hesitation, revoked their order, and I was allowed to join the

Army at Yorktown, but did not reach it until the business was

nearly over, the capitulation been signed in five or six days

after my arrival.

From thence I was sent with six regiments and ten pieces of

artilleray, to the aid of general Greene in South Carolina,

with orders to sweep, in my way, all those British Posts in

North Carolina; but they did not give me trouble, for, on my

taking direction towards Willmington, they abandoned that place

and every other post they had in that country, and left me at

liberty to pursue the march by the best and most direct route;

and on the 27th of December, I joined General Greene, near

Jacksonburgh.

[11]

The war was effectively over after this assignment and Arthur

St. Clair was furloughed and returned home in 1782. His

Ligonier estate, including the mill which he had opened for

communal use, was in ruins. Titles to his lands were not

carefully managed and squatters occupied key tracts. St. Clair

noted in a letter that he lost £20,000 on one piece of real

estate alone. His biographer William Henry Smith summed up his

homecoming plight: as:

The comfortable fortune, and the valuable offices, which were

all his in 1775, and eight years of the prime of life were all

gone ---- all given freely, and without regret, for freedom and

a republic.

[12]

St. Clair, though still a major-general, was elected to the

Pennsylvania Council of Censors. He was an active member and

drafted the report of the Censors, who were charged with

correcting defects in the Pennsylvania Constitution. St.

Clair's authored the recommendations calling for a new

Pennsylvania State constitutional Convention. The measure,

however, was defeated as less than 2/3rds of the People

supported the Resolution. In that same year he was elected

Vendue-master of Philadelphia (auctioneer) which was thought to

be a very lucrative position in City government. The victory in

the war left the State with a lot of property to be sold of

which St. Clair received a portion of the revenue. St. Clair

later, as the 9th President of the USCA, declared

that he lost money in that office fronting expenses that were

never reimbursed by the financially distressed city.

In the summer of 1783, while General St. Clair was still

discharging his duties as Vendue-master of Philadelphia, a

crisis gripped the confederation government that would doom it

from ever assembling at Independence Hall again. President

Boudinot and the United States in Congress Assembled on a hot

summer day were faced with a mutiny of soldiers in Philadelphia

surrounding their session at Independence Hall. USCA requested

that the Pennsylvania Supreme Council, also in session at

Independence Hall, call out the Pennsylvania militia but they

declined seeking to settle the mutiny peacefully. The mutineers

demands were made in very dictatorial terms, that,

unless their demand were complied with in twenty minutes, they

would let in upon them the injured soldiery, the consequences

of which they were to abide.

[13]

Word was immediately sent, by President Boudinot, to General

St. Clair and his presence requested. General St. Clair rushed

to the scene and confronted the mutineers. St. Clair then

reported to President Boudinot, Congress and the State

legislators of Pennsylvania his assessment and the demands of

the mutineers. Congress then directed him

... to endeavor to march the mutineers to their barracks,

and to announce to them that Congress would enter into no

deliberation with them; that they must return to Lancaster, and

that there, and only there, they would be paid.

After this, Congress appointed a committee to confer with the

executive of Pennsylvania, and adjourned awaiting St. Clair’s

signal that it was safe to evacuate the building. The Journals

of the United States in Congress report on Saturday, June 21,

1783:

The mutinous soldiers presented themselves, drawn up in the

street before the statehouse, where Congress had assembled. The

executive council of the state, sitting under the same roof,

was called on for the proper interposition. President DICKINSON

came in, and explained the difficulty, under actual

circumstances, of bringing out the militia of the place for the

suppression of the mutiny. He thought that, without some

outrages on persons or property, the militia could not be

relied on. General St. Clair, then in Philadelphia, was sent

for, and desired to use his interposition, in order to prevail

on the troops to return to the barracks. His report gave no

encouragement.

In this posture of things, it was proposed by Mr. IZARD, that

Congress should adjourn. It was proposed by Mr. HAMILTON, that

General St. Clair, in concert with the executive council of the

state, should take order for terminating the mutiny. Mr. REED

moved, that the general should endeavor to withdraw the troops

by assuring them of the disposition of Congress to do them

justice. It was finally agreed, that Congress should remain

till the usual hour of adjournment, but without taking any step

in relation to the alleged grievances of the soldiers, or any

other business whatever. In the meantime, the soldiers remained

in their position, without offering any violence, individuals

only, occasionally, uttering offensive words, and wantonly

pointing their muskets to the windows of the hall of Congress.

No danger from premeditated violence was apprehended, but it

was observed that spirituous drink, from the tip-pling-houses

adjoining, began to be liberally served out to the soldiers,

and might lead to hasty excesses. None were committed, however,

and, about three o'clock, the usual hour, Congress adjourned;

the soldiers, though in some instances offering a mock

obstruction, permitting the members to pass through their

ranks. They soon afterwards retired themselves to the barracks.

[14]

Thanks to Arthur St. Clair's ability to reason with the

mutineers, President Boudinot, the Delegates and the

Pennsylvania legislators passed through the files of the armed

soldiers without being physically molested.

President Boudinot on June 23rd wrote his brother

requesting his aid to protect Congress in what would be the new

Capitol of the United States.

My dear Brother Philada. 23 June 1783 -- I have only a moment

to inform you, that there has been a most dangerous

insurrection and mutiny among a few Soldiers in the Barracks

here. About 3 or 400 surrounded Congress and the Supreme

Executive Council, and kept us Prisoners in a manner near three

hours, tho' they offered no insult personally. To my great

mortification, not a Citizen came to our assistance. The

President and Council have not firmness enough to call out the

Militia, and allege as the reason that they would not obey

them. In short the political Maneuvers here, previous to that

important election of next October, entirely unhinges

Government. This handful of Mutineers continue still with Arms

in their hands and are privately supported, and it is well if

we are not all Prisoners in a short time. Congress will not

meet here, but has authorized me to change their place of

residence. I mean to adjourn to Princeton if the Inhabitants of

Jersey will protect us. I have wrote to the Governor

particularly. I wish you could get your Troop of Horse to offer

them aid and be ready, if necessary, to meet us at Princeton on

Saturday or Sunday next, if required.[15]

A committee, with Alexander Hamilton as chairman, waited

on the State Executive Council to insure the Government of the

United States protection in Philadelphia so Congress could

convene the following day. Elias Boudinot, however, received no

pledge of protection by the Pennsylvania militia and ordered

an adjournment of the USCA on June 24th to Princeton, New

Jersey. This was the last time the Confederation Congress

would convene in Pennsylvania.

The President issued and released this Proclamation to the

Philadelphia newspapers explaining the USCA’s move to

Princeton:

A Proclamation. Whereas a body of armed soldiers in the service

of the United States, and quartered in the barracks of this

city, having mutinously renounced their obedience to their

officers, did, on Saturday this instant, proceed under the

direction of their sergeants, in a hostile and threatening

manner to the place in which Congress were assembled, and did

surround the same with guards: and whereas Congress,

inconsequence thereof, did on the same day resolve, " That the

president and supreme executive council of this state should be

informed, that the authority of the United States having been,

that day, grossly insulted by the disorderly and menacing

appearance of a body of armed soldiers, about the place within

which Congress were assembled; and that the peace of this city

being endangered by the mutinous disposition of the said troops

then in the barracks, it was, in the opinion of Congress,

necessary, that effectual measures should be immediately taken

for supporting the public authority: and also, whereas Congress

did at the same time appoint a committee to confer with the

said president and supreme executive council on the

practicability of carrying the said resolution into due effect;

and also whereas the said committee have reported to me, that

they have not received satisfactory assurances for expecting

adequate and prompt exertions of this state for supporting the

dignity of the federal government ; and also whereas the said

soldiers still continue in a state off open mutiny and revolt,

so that the dignity and authority of the United States would be

constantly exposed to a repetition of insult, while Congress

shall continue to fit in this city; I do therefore, by and with

the advice of the said Committee, and according to the powers

and authorities in me vested for this purpose, hereby summon

the Honorable the Delegates composing the Congress of the

United States, and every of them, to meet in Congress on

Thursday the 26th of June instant, at Princetown, in the state

of New Jersey, in order that further and more effectual

measures may be taken for suppressing the present revolt, and

maintaining the dignity and authority of the United States; of

which all officers of the United States, civil and military,

and all others whom it may concern, are desired to take notice

and govern themselves accordingly.

President Boudinot chose Princeton for the seat of

government because he was a former resident, a Trustee of the

College of New Jersey, and his wife was from a prominent

Princeton Stockton family. Additionally, Princeton

was located approximately midway between New York and

Philadelphia and the College of New Jersey had a building large

enough in which the USCA could

assemble.

Assembled in Princeton, the USCA turned to a resolution

that was proposed by

Alexander Hamilton

ordering General Howe to march fifteen hundred troops to

Philadelphia to disarm the mutineers and bring them to

trial. The matter was sent to a committee. General

Washington had already taken action and dispatched the troops

in response to President Boudinot’s letter of the

21st requesting is aid. General Howe had

already arrived just outside of Princeton that evening writing

Commander-in-Chief Washington on the 1st

“I

arrived yesterday with the Troops within four Miles of this

Place where they will halt until twelve to Night.”

The following day, the USCA resolved:

That Major General Howe be directed to march such part of the

force under his command as he shall judge necessary to the

State of Pennsylvania; and that the commanding officer in the

said State he be instructed to apprehend and confine all such

persons, belonging to the army, as there is reason to believe

instigated the late mutiny; to disarm the remainder; to take,

in conjunction with the civil authority, the proper measures to

discover and secure all such persons as may have been

instrumental therein; and in general to make full examination

into all parts of the transaction, and when they have taken the

proper steps to report to Congress.[16]

With the resolution in hand, Howe set out for

Philadelphia. He spent the night of July

2nd encamped in Trenton and started crossing the

Delaware River into Pennsylvania the following morning. Near

Trenton Howe met with General St. Clair coming to Princeton and

he updated the general on the situation. General St. Clair

pressed on to Princeton and met with the President that

evening. Boudinot wrote General Washington:

General S'. Clair is now here, and this moment suggests an Idea

which he had desired me to mention to your Excellency, as a

Matter of Importance in his View of the Matter in the intended

Inquiry at Philadelphia.— That the Judge Advocate should be

directed to attend the Inquiry — By this Means the Business

would be conducted with most Regularity — The Inquiry might be

more critical, and as several of the Officers are in Arrest,

perhaps a Person not officially engaged, may Consider himself

in an invidious Situation — It is late at Night, and no

possibility of obtaining the Sense of Congress, and therefore

your Excellency will consider this as the mere Suggestion of an

individual & use your own Pleasure.[17]

George Washington, after receipt of the letter, ordered Judge

Advocate Edwards to repair at once to Philadelphia.[18]

The USCA resolution directing General Howe to move with the

troops against the mutineers affronted

General St. Clair

and he regarded it as an attempt to supersede his command and

undermine his negotiations. General St. Clair took it upon

himself to write Congress the following letter:

[General Howe came to

enquire into the conduct of the officers and Sergeants after

the Mutiny that drove Congress from

Philadelphia]

Sir, When I had the honour

to wait upon you at Princetown I was pleased to find that

General Howe had been ordered to Pennsylvania and at the same

time I was flattered to hear, as I did, from several of the

members of Congress that It was left at my discretion either

to direct the enquiry into the late disorders amongst the

troops this State, or leave it entirely to him. For though it

was not more than had a right to expect it was a piece of

attention that could not fail to be

gratifying.

At the time I left

Princetown I had determined to leave the matter entirely to

General Howe, but upon selection finding myself in command in

this state, having been called to it by the secretary at War

previous to his departure for Virginia and that I had also

been brought into view by Congress, it struck me that another

officer taking up the business would have an odd appearance

and must beget sentiments unfavorable to me. I therefore

acquainted General Howe that I had understood the Resolution

of Congress left me, at least an option. [struck out -

"justify the appointment of a Junior Officer to carry into

effect what a Senior had began"] I read the Resolution and

understood it as he did that the business was to be conducted

by him; but upon reconsidering it, the expressions I see will

admit of another construction. I wish they had been more

explicit on my own account, because if they had, there could

have been no doubt about the line I should pursue, nor could

there have been insinuations (underlined) to my prejudice. My

conduct must have been either satisfactory to congress or not

-- if not, the instances should have been pointed out, and I

might have defended myself, but against an implied censure,

there is no defence, and nothing in my opinion but

incompetence or worse, can justify the appointment of a

junior officer to carry into effect what a senior officer had

began. On General Howe's because he might have found himself

in a disagreeable circumstances from not fully comprehending

the views of congress and my situation. I beg Sir I may not

be misunderstood. I am not soliciting to be continued in

command here. I have the highest respect for Congress but I

owe something to myself also, and I have to declare to them

in the most express terms, that I can take no farther command

in the State and to require that they will please to direct

the Secretary at War to order General Howe or some other

officer to manage the business of dismissing the Pennsylvania

line.* I have been long enough in publick life to know that

there are injuries a man must bear they have and been so

often repeated to me as to have rendered me callous, nor are

the conversations that arise from them the less poignant that

cooperation cannot be demanded. I have the honour to be sir,

etc,.

*To General Howe I

shall afford all the assistance I can and shall attend the

court Martials as an evidence whenever I receive notice of

its being convened.

President

Elias Boudinot chose not to bring the letter before Congress

replying:

I duly recd your favor of yesterday but conceiving that you had

mistaken the Resolution of Congress, I showed it to Mr.

Fitzsimmons and we have agreed not to present it to Congress,

till we hear again from you. Congress were so careful to

interfere one way or the other in the military etiquette, that

we recommitted the Resolution to have everything struck out

that should look towards any determination as to the Command,

and it was left so that the Commanding officer be him who it

might, was to carry the Resolution into Execution; and it can

bear no other Construction. If on the second reading you

choose your Letter should be read in Congress, it shall be done

without delay.

I have the honour to be with Great respect

Your very Humble Servt

Elias Boudinot, President

P. S., You may depend on Congress having been perfectly

satisfied with your conduct.

[19]

Boudinot undoubtedly trusted St. Clair’s judgment and spared

him the embarrassment of making his letter known to Congress.

William Henry Smith, the complier of Arthur St. Clair’s Papers

concludes his chapter on this incident stating:

While

St. Clair was engaged in closing up the accounts and furloughing

the veteran soldiers, in 1783, the new levies, stationed at

Lancaster, refusing to accept their discharges without immediate

pay, mutinied and marched for Philadelphia, for the avowed

purpose of compelling Congress to accede to their demands. The

mutineers were reinforced by the recruits in the barracks of

Philadelphia, and, as they marched to the hall where Congress was

in session, they numbered three hundred. Their demand was made in

very peremptory terms, that, "unless their demand was complied

with in twenty minutes, they would let in upon them the injured

soldiery, the consequences of which they were to abide." Word was

immediately sent to General St. Clair, and his presence

requested. After hearing a statement of the facts by him,

Congress directed him to endeavor to march the mutineers to their

barracks, and to announce to them that Congress would enter into

no deliberation with them; that they must return to Lancaster,

and that there, and only there, they would be paid.1 After this,

Congress appointed a committee to confer with the executive of

Pennsylvania, and adjourned. The members passed through the files

of the mutineers, without being

molested.

The

committee, with Alexander Hamilton as chairman, waited on the

State Executive Council; but, receiving no promise of

protection, on the 24th of June, advised an adjournment of

Congress to Princeton. The day after their arrival there, a

resolution was passed directing General Howe to march fifteen

hundred troops to Philadelphia to disarm the mutineers and

bring them to trial. Before this force could reach

Philadelphia, St. Clair and the Executive Council had succeeded

in quieting the disturbance without bloodshed. The principal

leaders were arrested, obedience secured, after which Congress

granted a pardon. The resolution directing General Howe to move

with the troops, gave offense to General St. Clair, who

regarded it as an attempt to supersede him in his command.

Thereupon, he addressed a sharp letter to the President of

Congress, who very considerately refrained from laying it

before that body. Explanations followed, showing that St. Clair

had misconstrued the order, and peace prevailed once

more. [20]

It was not until two years later that Arthur St. Clair

would enter onto the stage of national politics. In

November of 1785 he was elected a Pennsylvania delegate to the

USCA and joined the ranks of the same body he freed from the

military mutiny two years earlier. His tenure as a

delegate to the USCA was plagued with quorum failures. By

January 1, 1787, the USCA had gone almost two months without

forming a quorum and replacing President Gorham who had

returned to Massachusetts in early November

1786.

So paralyzed was the federal government that on January

12th, when Massachusetts General William Shepard

wrote to Knox

[21]

pleading with him to endorse the

decision to arm 900 local militia using guns and ammunition

commandeered from the U.S. Arsenal he was marching on to

protect at Springfield, Knox replied that he lacked authority

to give that permission. That authority, Knox wrote, rested

with the United States Congress, which was not currently in

session. General Shepard decided to go ahead without

Knox’s permission lest the Arsenal "fall into into Enemies

from too punctilious observance of Forms." Shepard

reached the armory before Shays and commandeered the weapons

stored there.

|

Click Here to view the US Mint & Coin Acts 1782-1792

|